Why is nobody using Refinements?

Future relevancy protection: As Tim Garnett correctly points out, at lot of discussion of Refinements suffers from not being clear about which version of Ruby is current at the time of writing. When I gave this talk, the latest version of Ruby was 2.2.3, but I believe the content is still relevant for 2.3.

This is a transcript of a presentation I gave at RubyConf 2015; the actual slides are here; the video is from confreaks.

Chances are, you’ve heard of refinements, but never used them.

The Refinements feature has existed as a patch and subsequently an official part of Ruby for around five years, and yet to most of us, it only exists in the background, surrounded by a haze of opinions about how they work, how to use them and, indeed, whether or not using them is a good idea at all.

I’d like to spend a little time taking a look at what Refinements are, how to use them and what they can do.

Disclaimer

But don’t get me wrong - this is not a sales pitch for refinements! I am not going to try to convince you that they will solve all your problems and that you should all be using them!

The title of this presentation is “Why is nobody using refinements?” and that’s a genuine question. I don’t have all the answers!

My only goal is that, by the end of this, both you and I will have a better understanding of what they actually are, what they can actually do, when they might be useful and why it might be that they’ve lingered in the background for so long.

What are refinements?

Simply put, refinements are a mechanism to change the behaviour of an object in a limited and controlled way.

By change, I mean add new methods, or redefine existing methods on an object.

By limited and controlled, I mean that adding or changing those methods does not have an impact on other parts of our software which might interact with that object.

Let’s look at a very simple example:

module Shouting refine String do def shout self.upcase + "!" end end end

Refinements are defined inside a module, using the refine method.

This method accepts a class – String, in this case – and a block, which contains all the methods to add to that class when the refinement is used. You can refine as many classes as you want within the module, and define as many methods are you’d like within each block.

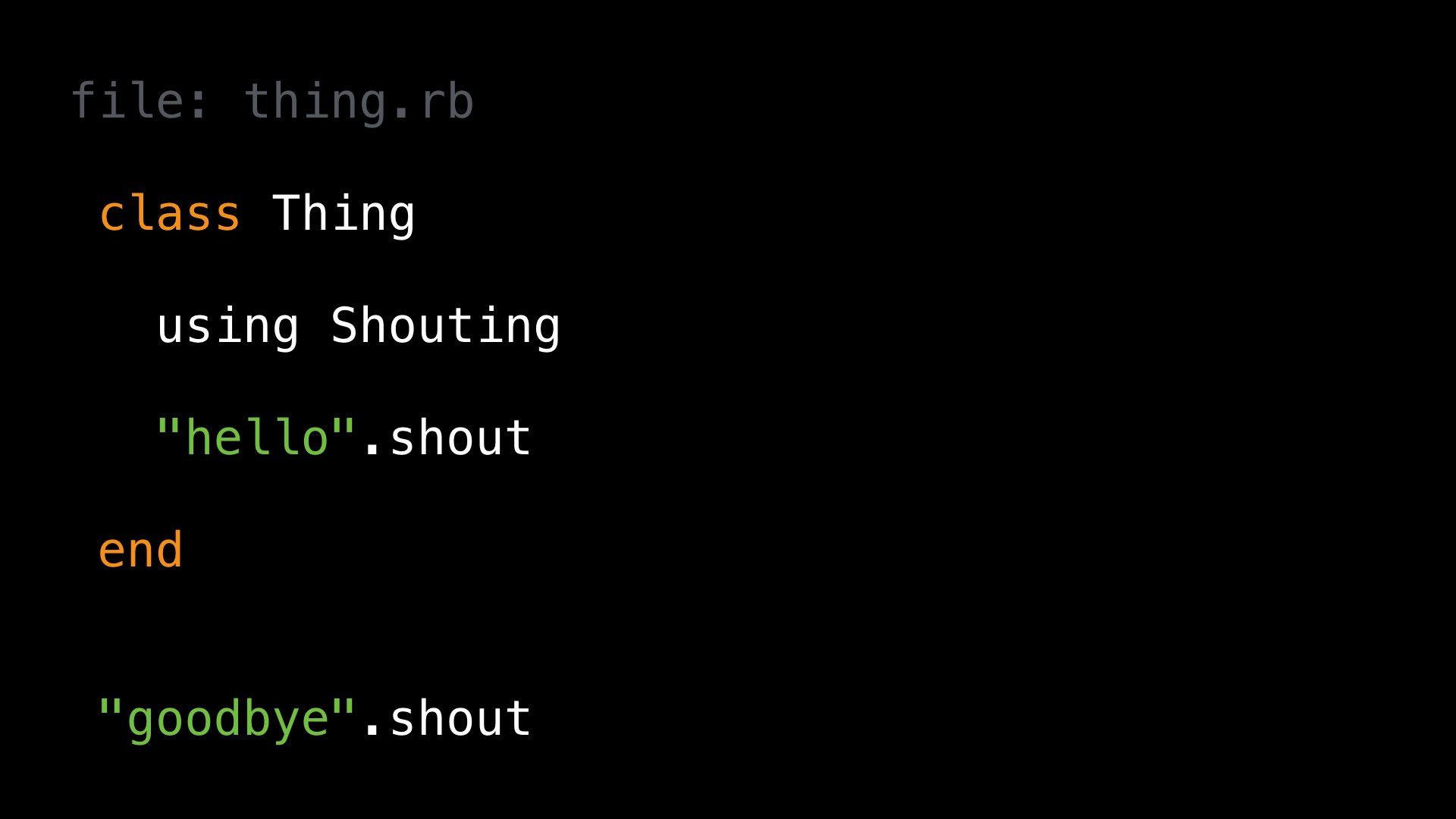

To use a refinement, we call the using method with the name of the enclosing module.

class Thing using Shouting "hello".shout # => "HELLO!" end

When we do this, all instances of that class, within the same scope as our using call, will have the refined methods available.

Another way of saying that is that the refinement has been “activated” within this scope.

However, any strings outside that scope are left unaffected:

"hello".shout # => NoMethodError: undefined method 'shout' for "Oh no":String

Changing existing methods

Refinements can also change methods that already exist

module TexasTime refine Time do def to_s if hour > 12 "Afternoon, y’all!" else super end end end end

When the refinement is active, it is used instead of the existing method (although the original is still available via the super keyword, which is very useful).

class RubyConf using TexasTime Time.parse("12:00").to_s # => "2015-11-16 12:00:00" Time.parse("14:15").to_s # => "Afternoon, y’all!" end

Anywhere the refinement isn’t active, the original method gets called, exactly as before.

Time.parse("14:15").to_s # => "2015-11-16 14:15:00"

And that’s really all there is to refinements – two new methods, refine, and using.

However, there are some quirks, and if we really want to properly understand refinements, we need to explore them. And the best way of approaching this, is by considering a few more simple examples.

Using using

Now we know that we can call the refine method within a module to create refinements, and that’s all relatively straightforward, but it turns out that where and when you call the using method has a profound effect on how the refinement behaves with our code.

We’ve seen that invoking using inside a class definition works. We activate the refinement, and we can call refined methods on a String instance:

class Thing using Shouting "hello".shout # => "HELLO!" end

But we can also move the call to using somewhere outside the class, and still use the refined method as before.

using Shouting class Thing "hello".shout # => "HELLO!" end

In the examples so far we’ve just been calling the refined method directly, but we can also use them within methods defined in the class.

class Thing using Shouting def greet "hello".shout end end Thing.new.greet # => "HELLO!"

Again, even if the call to using is outside of the class, our refined behaviour still works.

using Shouting class Thing def greet "hello".shout end end Thing.new.greet # => "HELLO!"

But this doesn’t work:

class Thing using Shouting def greet "hello" end end Thing.new.greet.shout! # => NoMethodError

We can’t call shout on the String returned by our method, even though that String object was created within a class where the refinement was activated.

And here’s another broken example:

class Thing using Shouting end class Thing "hello".shout # => NoMethodError end

We’ve activated the refinement inside our class, but when we reopen the class and try to use the refinement, we get NoMethodError again.

If we nest a class within another where the refinement is active, it seems to work:

class Thing using Shouting class OtherThing "hello".shout # => "HELLO!" end end

But it doesn’t work in subclasses:

class Thing using Shouting end class OtherThing < Thing "hello".shout # => NoMethodError end

Unless they are also nested classes:

class Thing using Shouting class OtherThing < Thing "hello".shout # => "HELLO!" end end

And even though nested classes work, if you try to define a nested class using the “double-colon” or “compact form”, our refinements have disappeared again:

class Thing using Shouting end class Thing::OtherThing "hello".shout # => NoMethodError end

Even blocks might seem to act strangely:

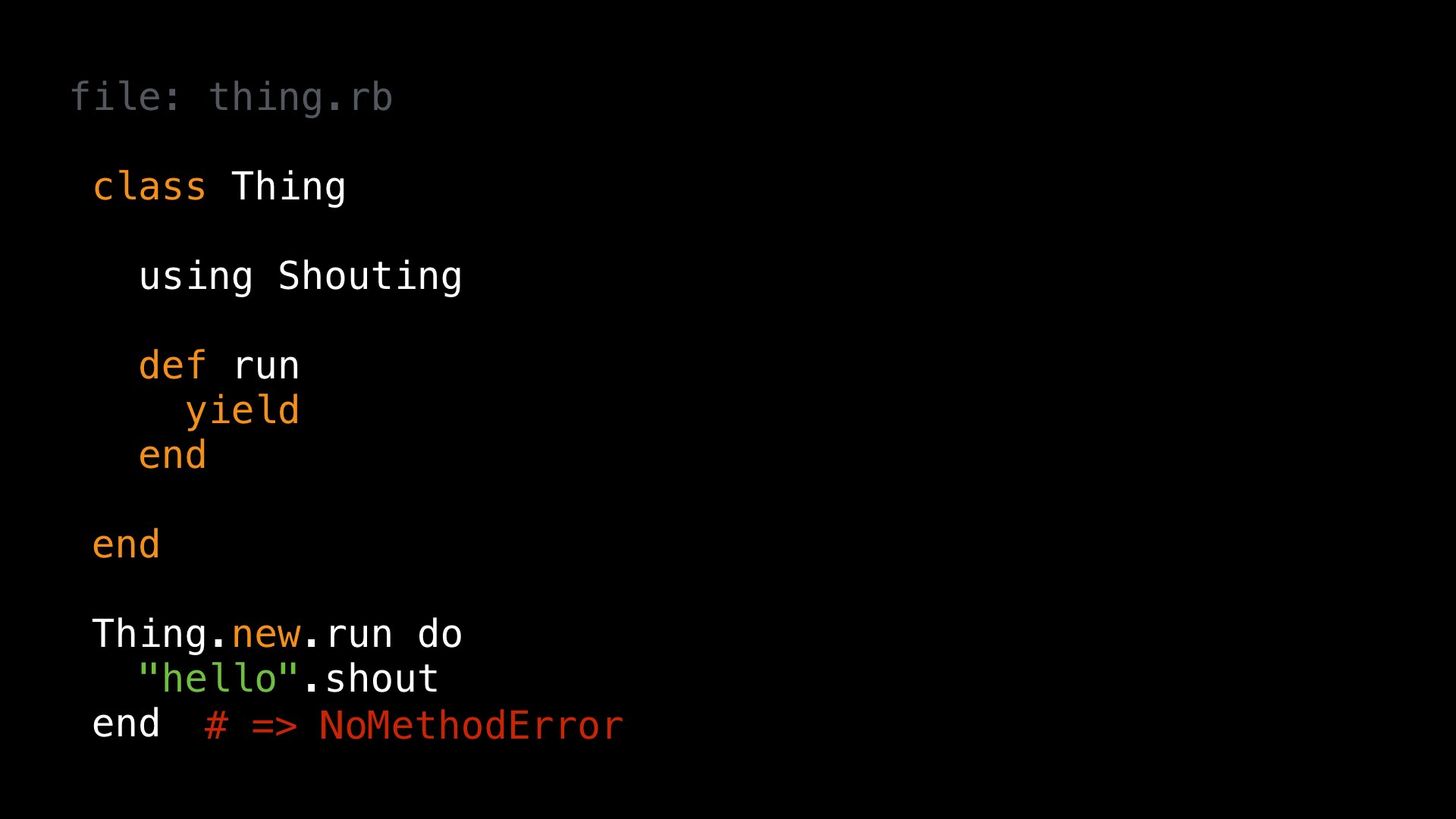

class Thing using Shouting def run yield end end Thing.new.run do "hello".shout end # => NoMethodError

Our class uses the refinement, but when we pass a block to a method in that class, suddenly it breaks.

So what’s going on here? For many of us this is quite counter-intuitive; after all, we’re used to being able to re-open classes, or share behaviour between super- and sub-classes, but it seems like that only works intermittently with refinements?

It turns out that the key to understanding how and when refinements are available relies on another aspect of how Ruby works that you may have already heard of, or even encountered directly.

The key to understanding refinements is understanding about lexical scope.

Lexical scope

To understand about lexical scope, we need to learn about some of the things that happen when Ruby parses our program.

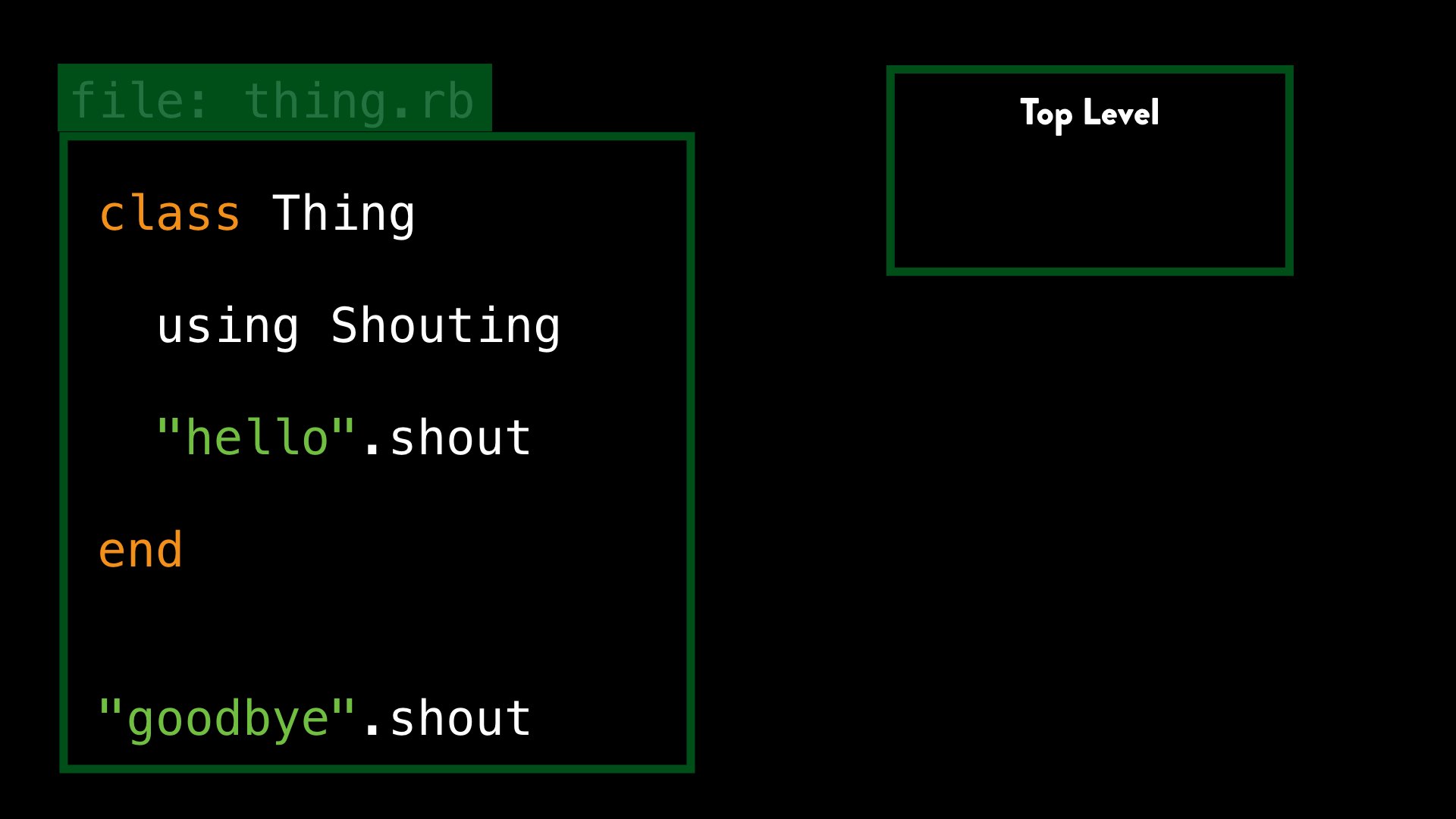

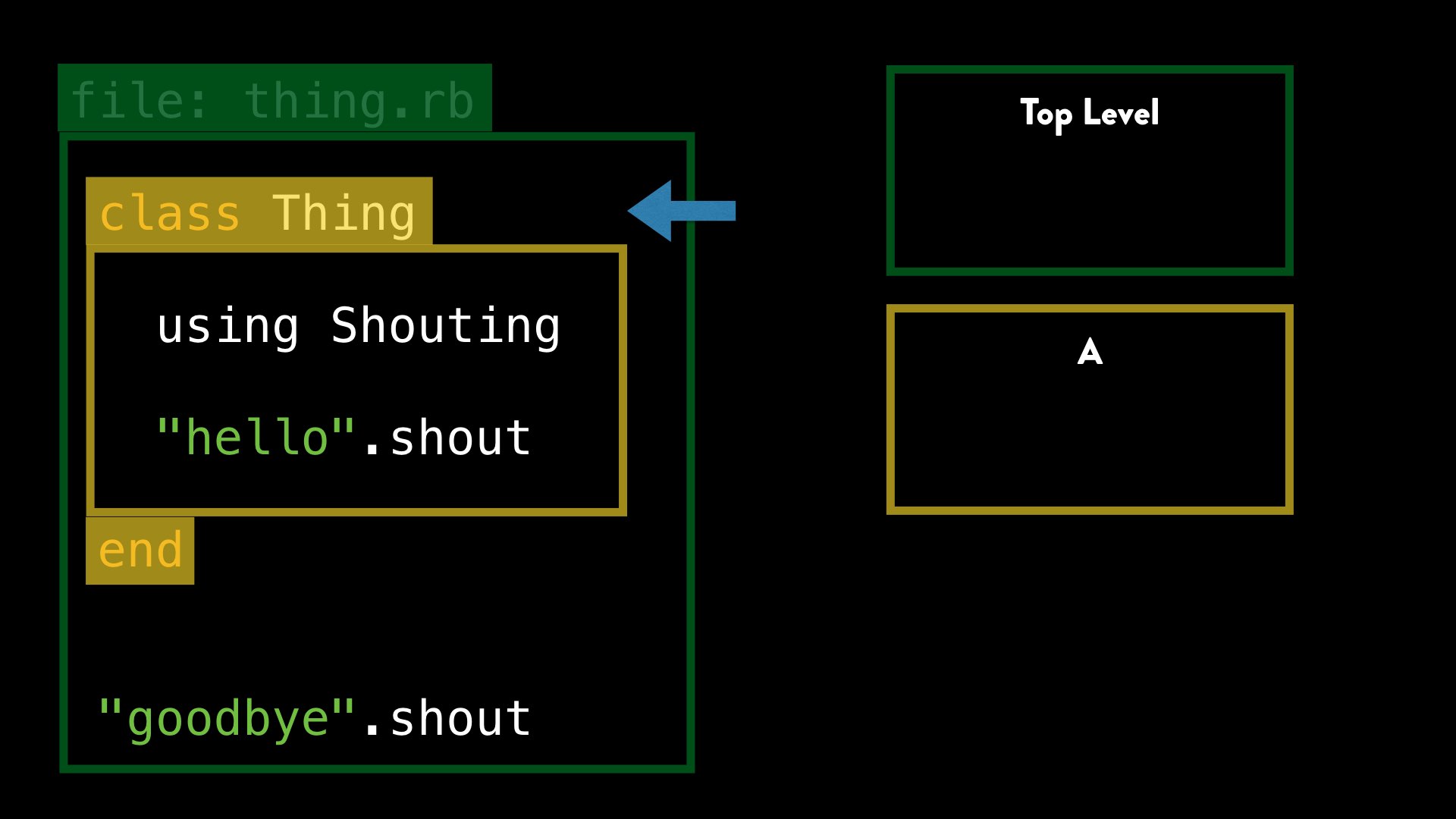

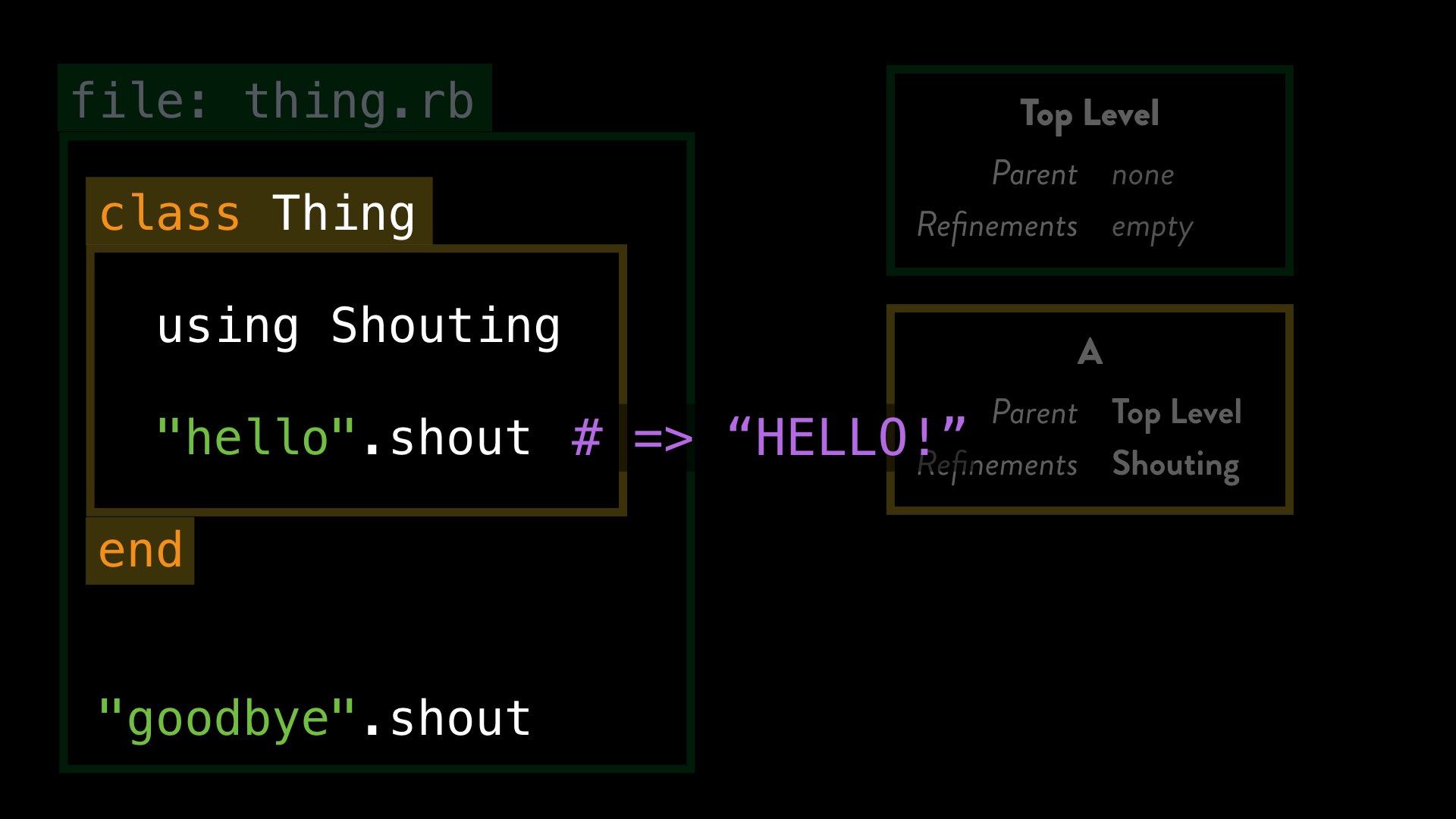

Let’s look at the first example again:

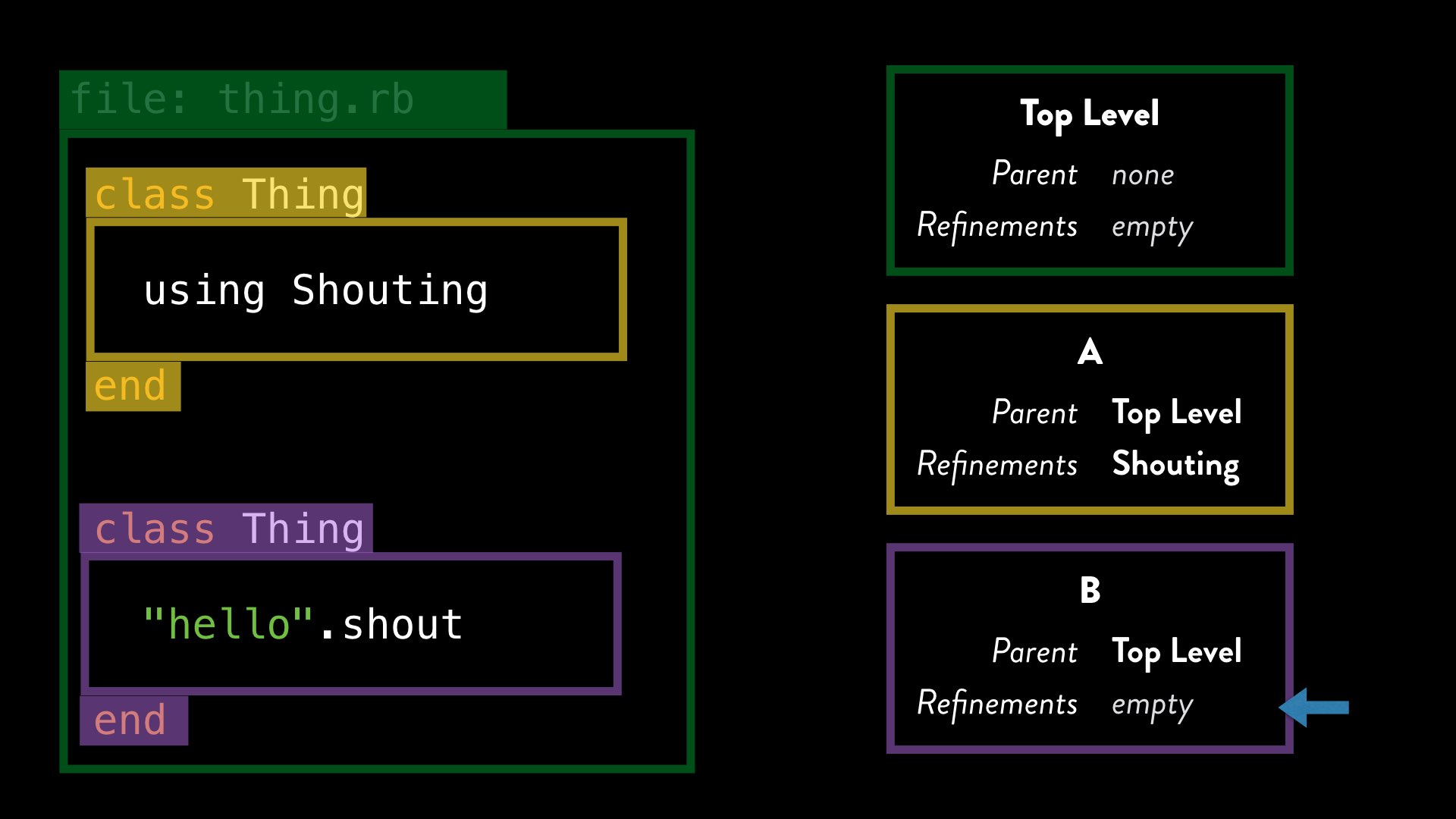

As Ruby parses this program, it is constantly tracking a handful of things to understand the meaning of the program. Exploring these in detail would take a whole presentation in itself, but for the moment, the one we are interested in is called the “current lexical scope”.

Let’s “play computer” and follow Ruby as it processes our simple program here.

The top-level scope

When Ruby starts parsing the file, it creates a new structure in memory – a new “lexical scope” – which holds various bits of information that Ruby uses to track what’s happening at that point. We call this the “top-level” lexical scope.

When we encounter a class (or module) definition, as well as creating the class and everything that involves, Ruby also creates a new lexical scope, nested “inside” the current one.

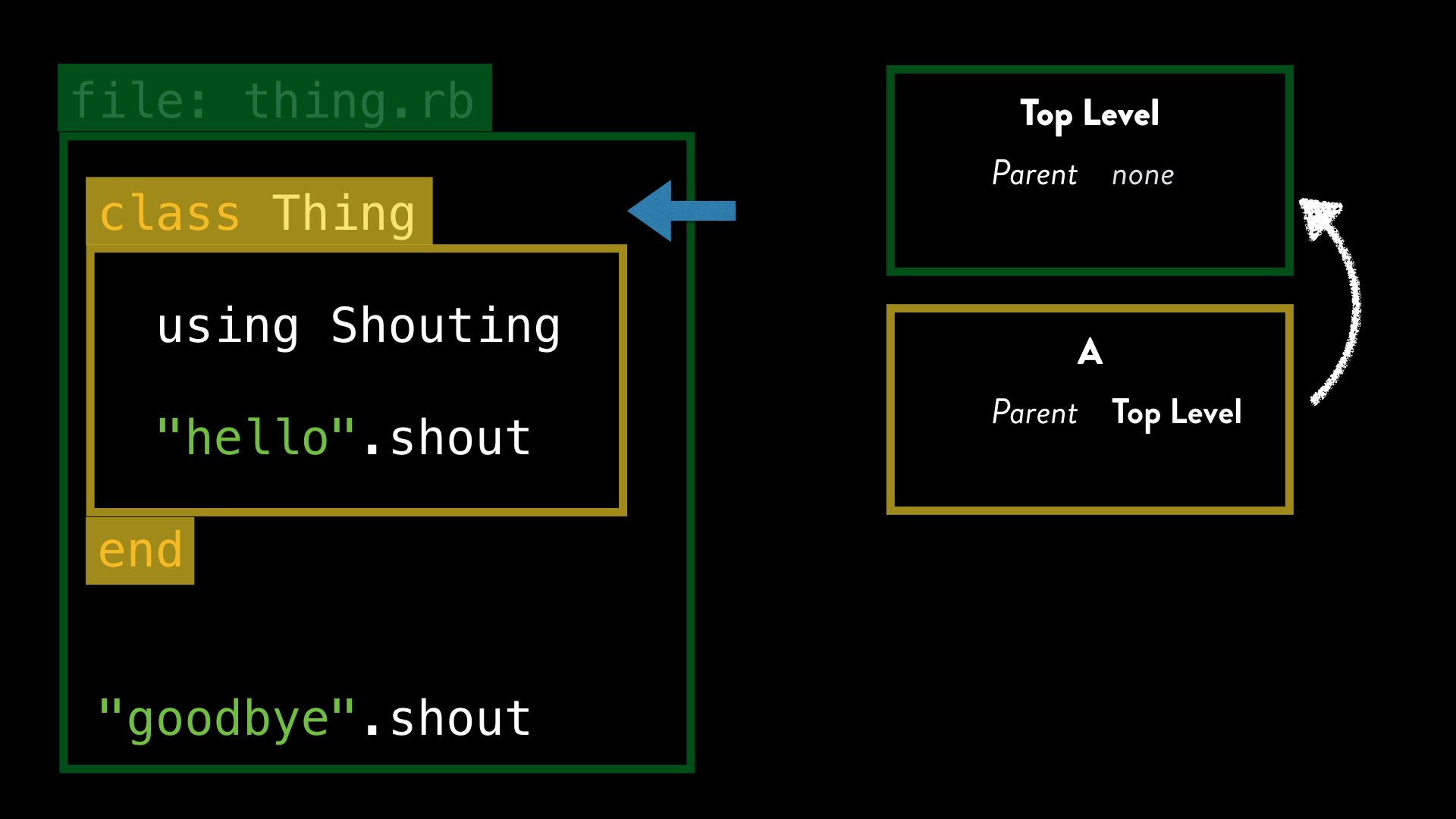

We can call this lexical scope “A”, just to give it an easy label. Visually it makes sense to show these as nested, but behind the scenes this relationship is modelled by each scope linking to its parent. “A”’s parent is the top level scope, and the top level scope has no parent.

As Ruby processes all the code within this class definition, the “current” lexical scope is now A.

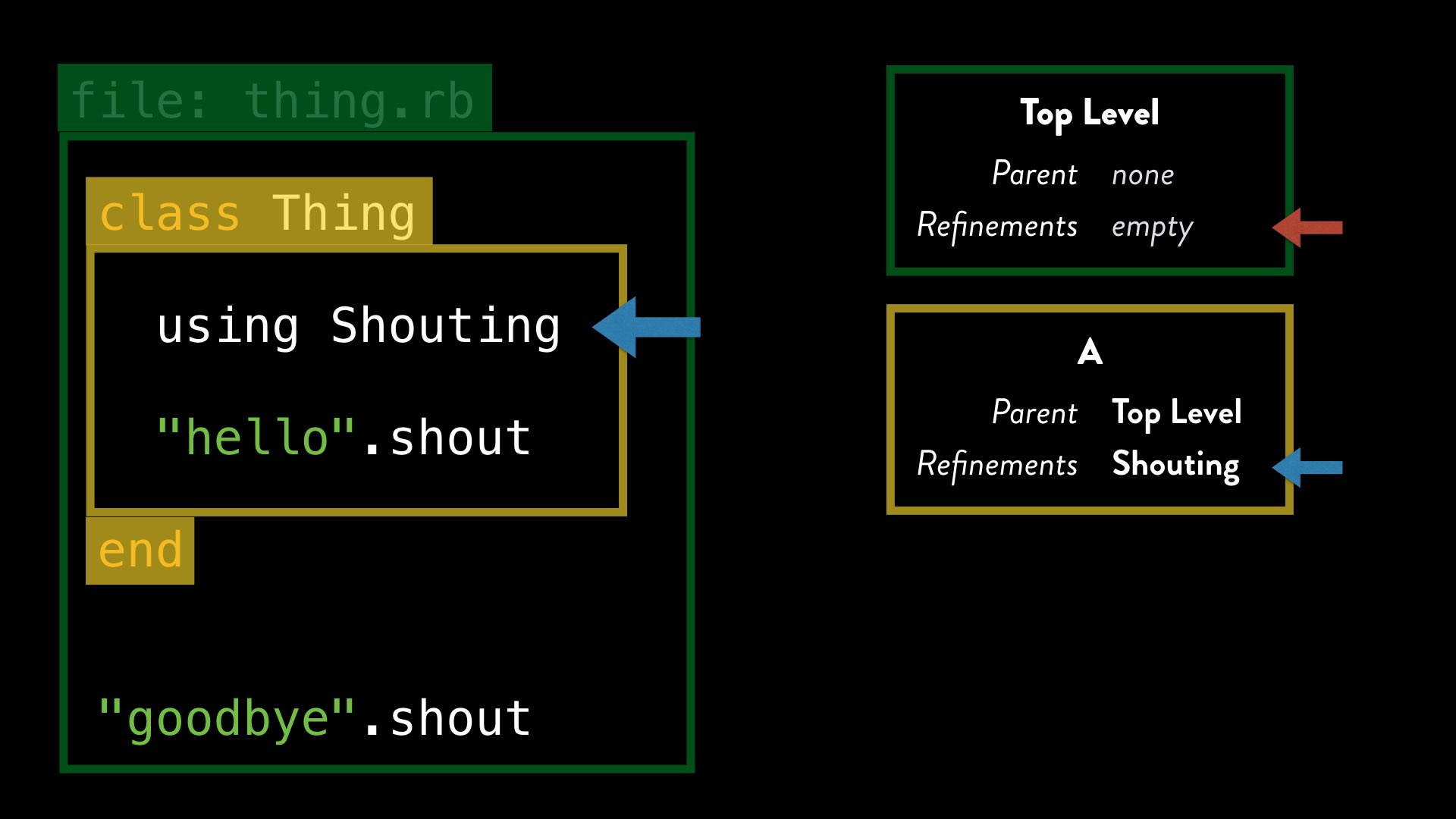

When we call using, Ruby stores a reference to the refinement within the current lexical scope. We can also say that within lexical scope “A”, the refinement has been activated.

We can see now that there are no activated refinements in the top-level scope, but our Shouting refinement is activated for lexical scope A.

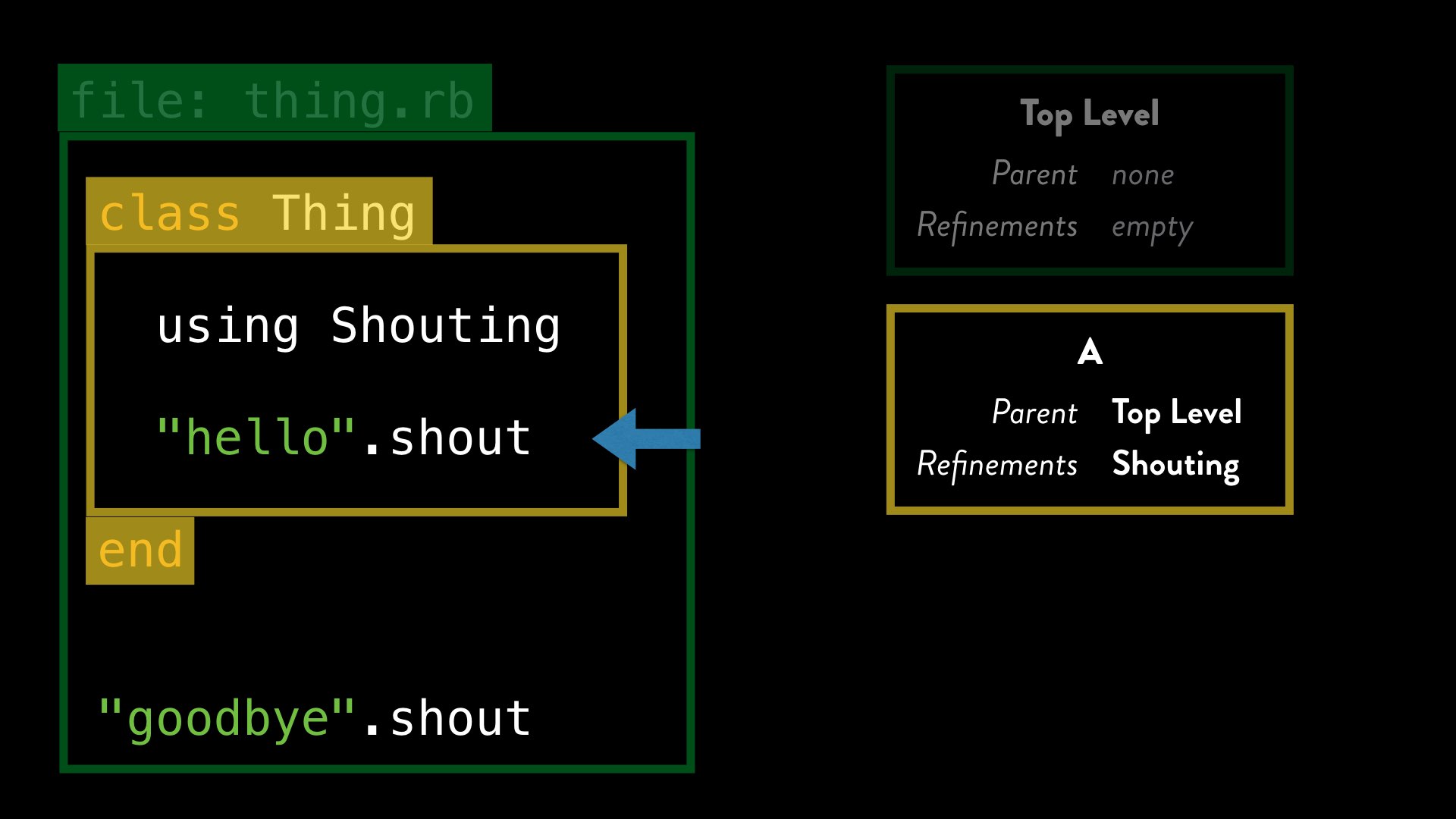

Next, we can see a call to the method shout on a String instance. The details of method dispatch are complex and interesting in their own right, but one of the things that happens at this point is that Ruby checks to see if there are any activated refinements in the current lexical scope that might affect this method.

In this case, we can see that for current lexical scope “A”, there is an activated refinement for the shout method on Strings, which is exactly what we’re calling.

Ruby then looks up the correct method body within the refinement module, and invokes that instead of any existing method.

And there, we can see that our refinement is working as we hope.

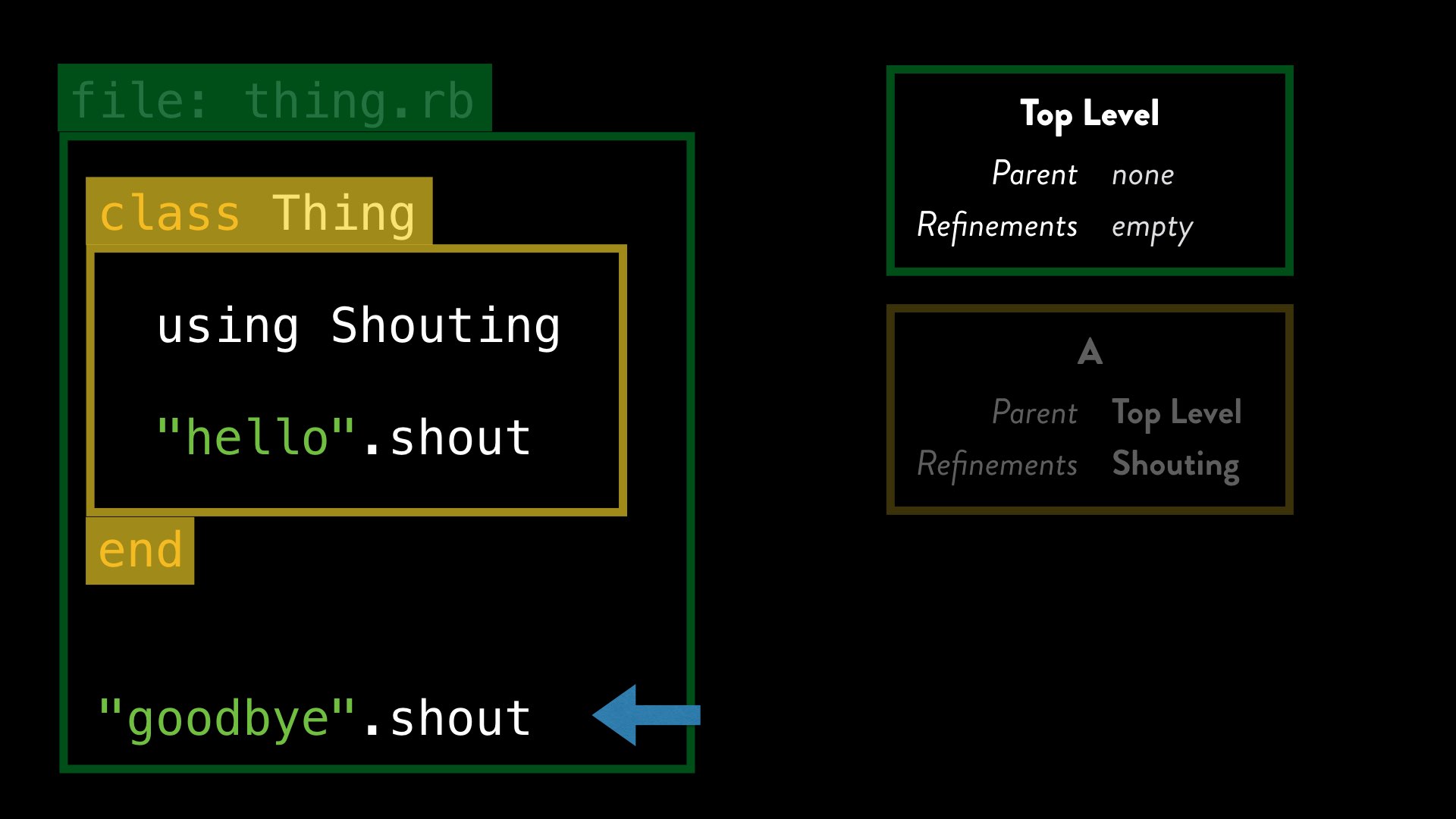

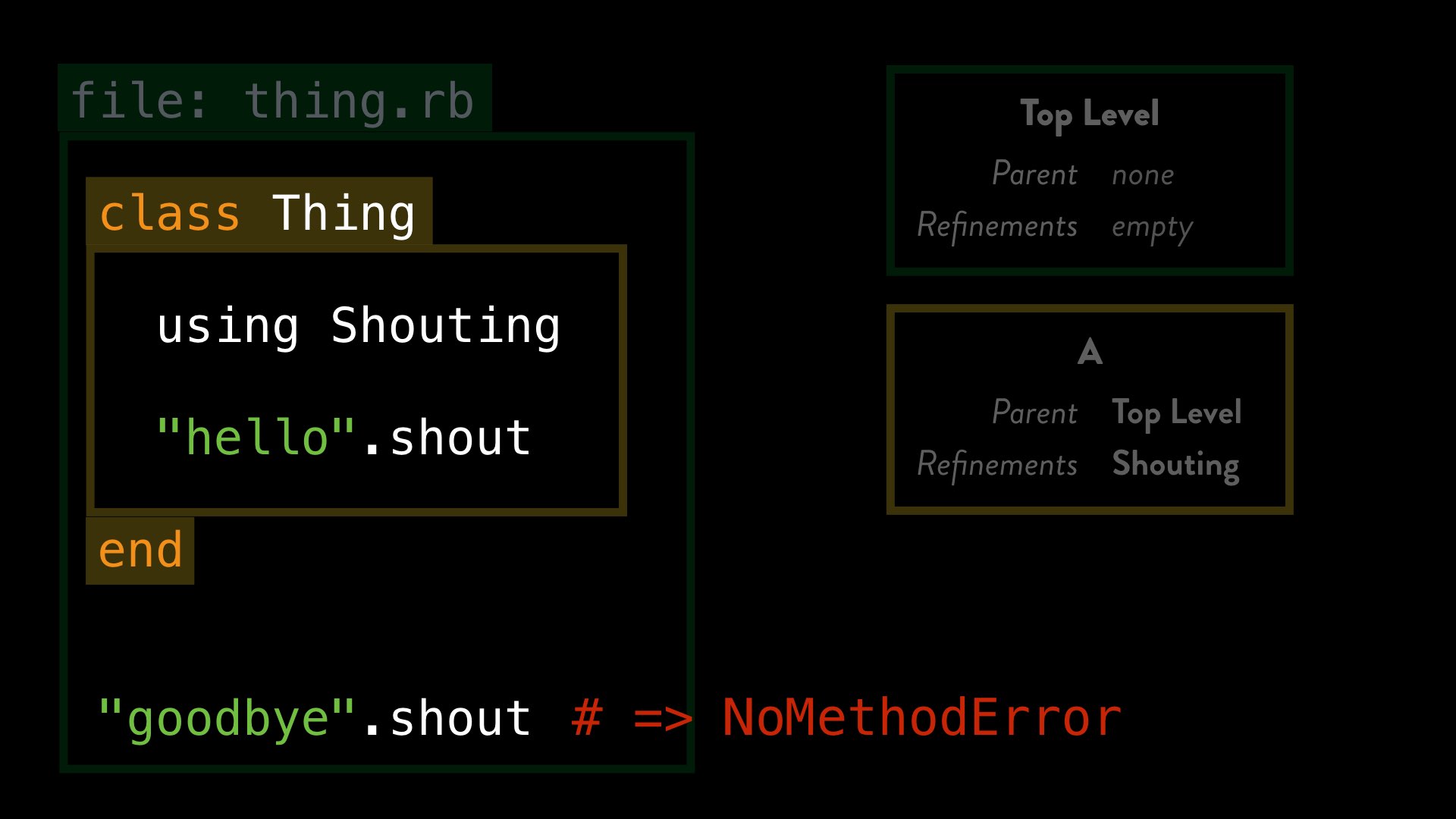

So what about when we try and call the method later? Well, once we leave the class definition, the current lexical scope returns to being the parent, which is the top-level one.

Then we find our second String instance and a method being called on it.

Once again, when ruby dispatches for the shout method, it checks the current lexical scope – the top-level one – for the presence of any refinements, but in this case, there are none. Ruby behaves as normal, which is to call method_missing and this will raise an exception by default.

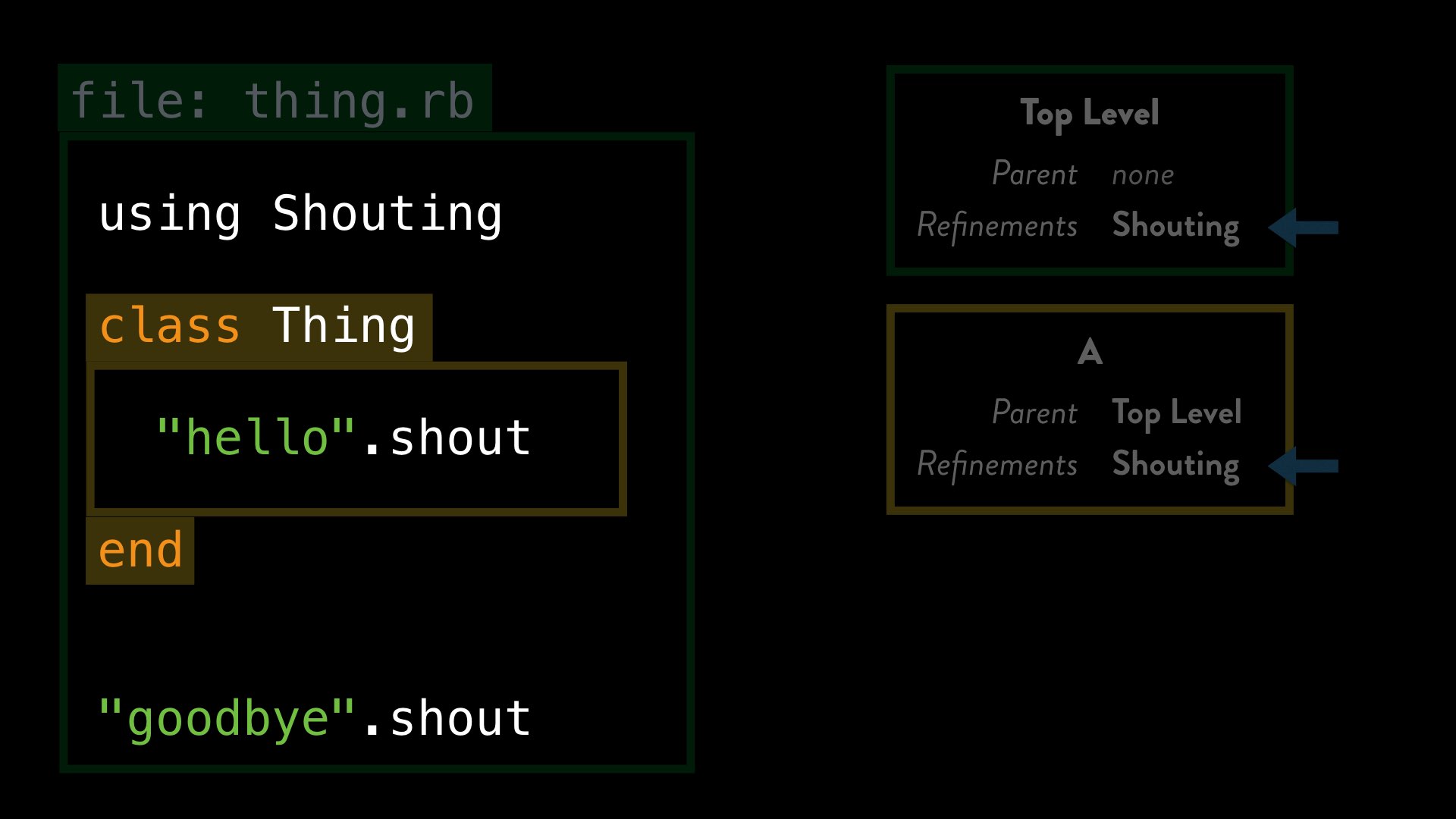

Calling using at the top-level

If we had called using Shouting outside of the class, at the top level, our use of the refined method both inside and outside the class works perfectly.

This is because once a refinement is activated, it is activated for all nested scopes, so calling using at the top level activated the refinement in the top level scope, which means it will be activated in any nested scopes, including “A”. And so, our call to the refined method within the class works too.

So this is our first principle of how refinements work:

When we activate a refinement with the using method, that refinement is active in the current and any nested lexical scopes.

However, once we leave that scope, the refinement is no longer activated, and Ruby behaves as it did before.

Lexical scope and re-opening classes

Let’s look at another example from earlier. Here we define a class, and activate the refinement, and later re-open that class and try to use it. We’ve already seen that this doesn’t work; the question is why.

Watching Ruby build its lexical scopes reveals why this is the case. Once again, the first class definition gives us a new, nested lexical scope A. It’s within this scope, that we activate the refinements. Once we reach the end of that class definition, we return to the top level lexical scope.

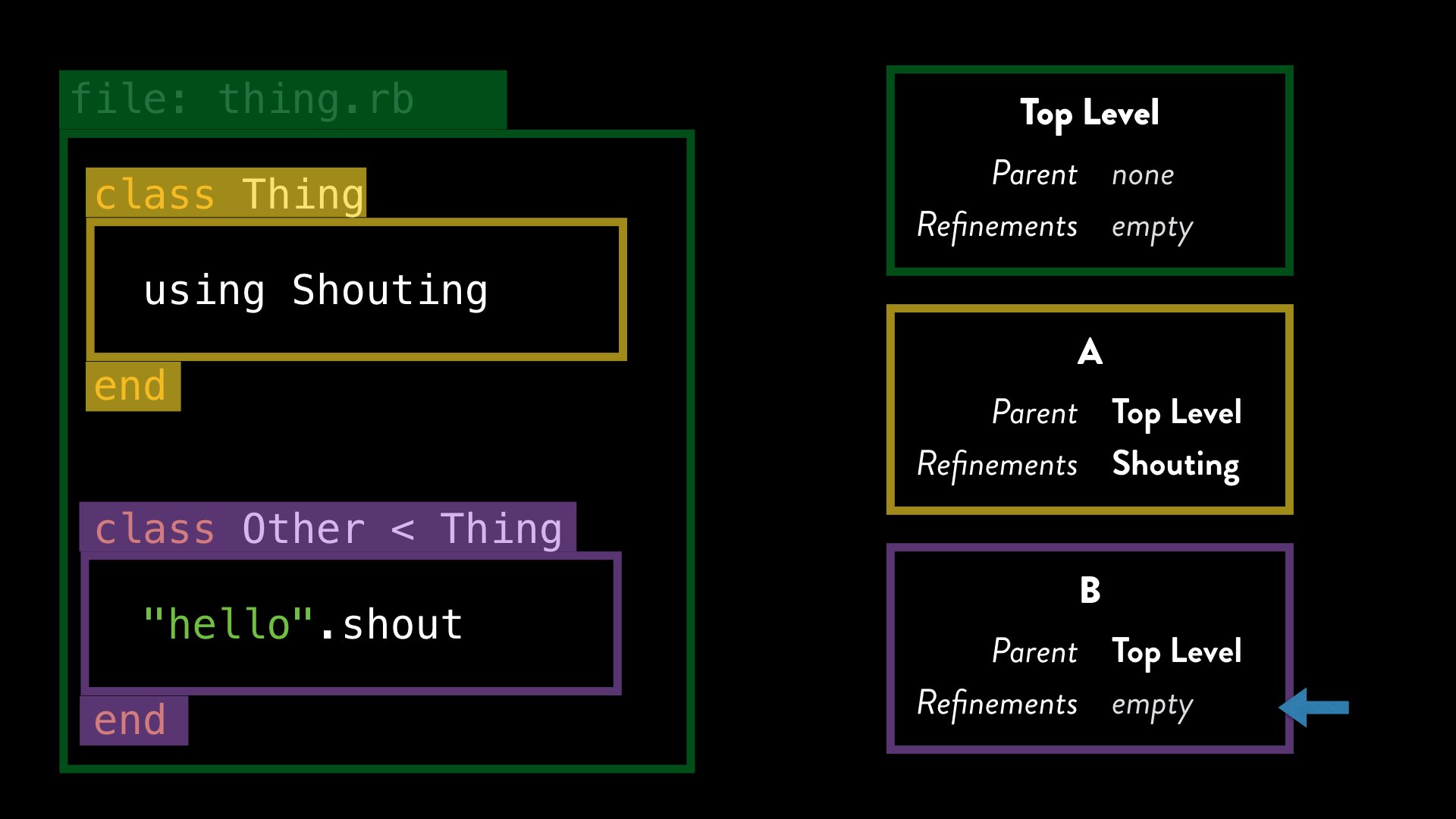

When we re-open the class, Ruby creates a nested lexical scope as before, but it is distinct from the previous one. Let’s call it B to make that clear.

While the refinement is activated in the first lexical scope, when we re-open the class, we are in a new lexical scope, and one where the refinements are no longer active.

So our second principle is this:

Just because the class is the same, doesn’t mean you’re back in the same lexical scope.

This is also the reason why our example with subclasses didn’t behave as we might’ve expected:

It should be clear now, that the fact that we are within a subclass actually has no bearing on whether or not the refinement is activated; it’s entirely determined by lexical scope. Any time Ruby encounters a class or module definition via the class (or module) keywords, it creates a new, fresh, lexical scope, even if that class (or module) has already been defined somewhere else.

This is also the reason why, even when activated at the top-level of a file, refinements only stay activated until the end of that file – because each file is processed using a new top-level lexical scope.

So now we have another two principles about how lexical scope and refinements work.

Just as re-opened classes have a different scope, so do subclasses. In fact:

The class hierarchy has nothing to do with the lexical scope hierarchy.

We also now know that every file is processed with a new top-level scope, and so refinements activated in one file are not activated in any other files – unless those other files also explicitly activate the refinement.

Lexical scope and methods

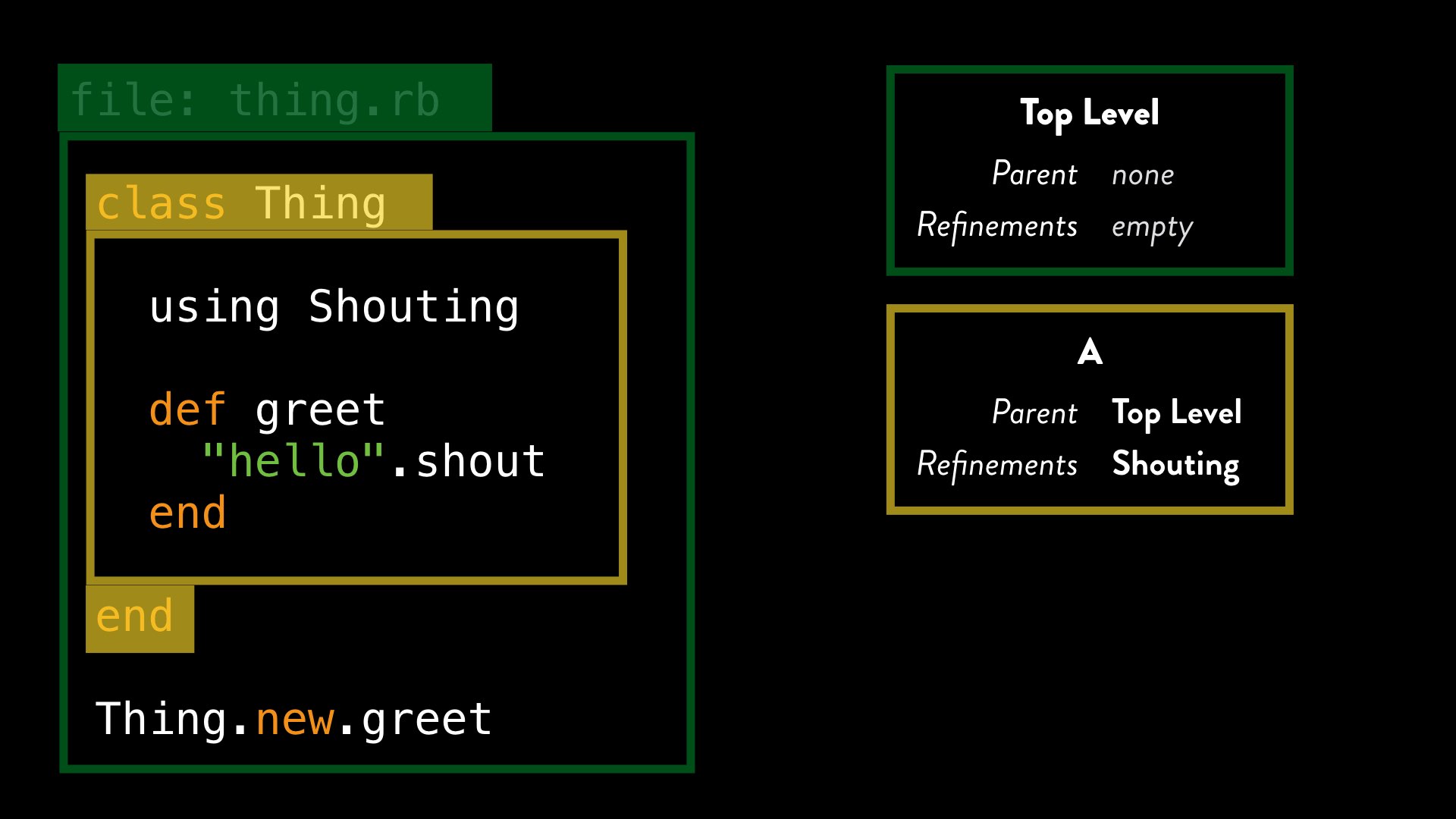

Let’s look at one more of our examples from earlier:

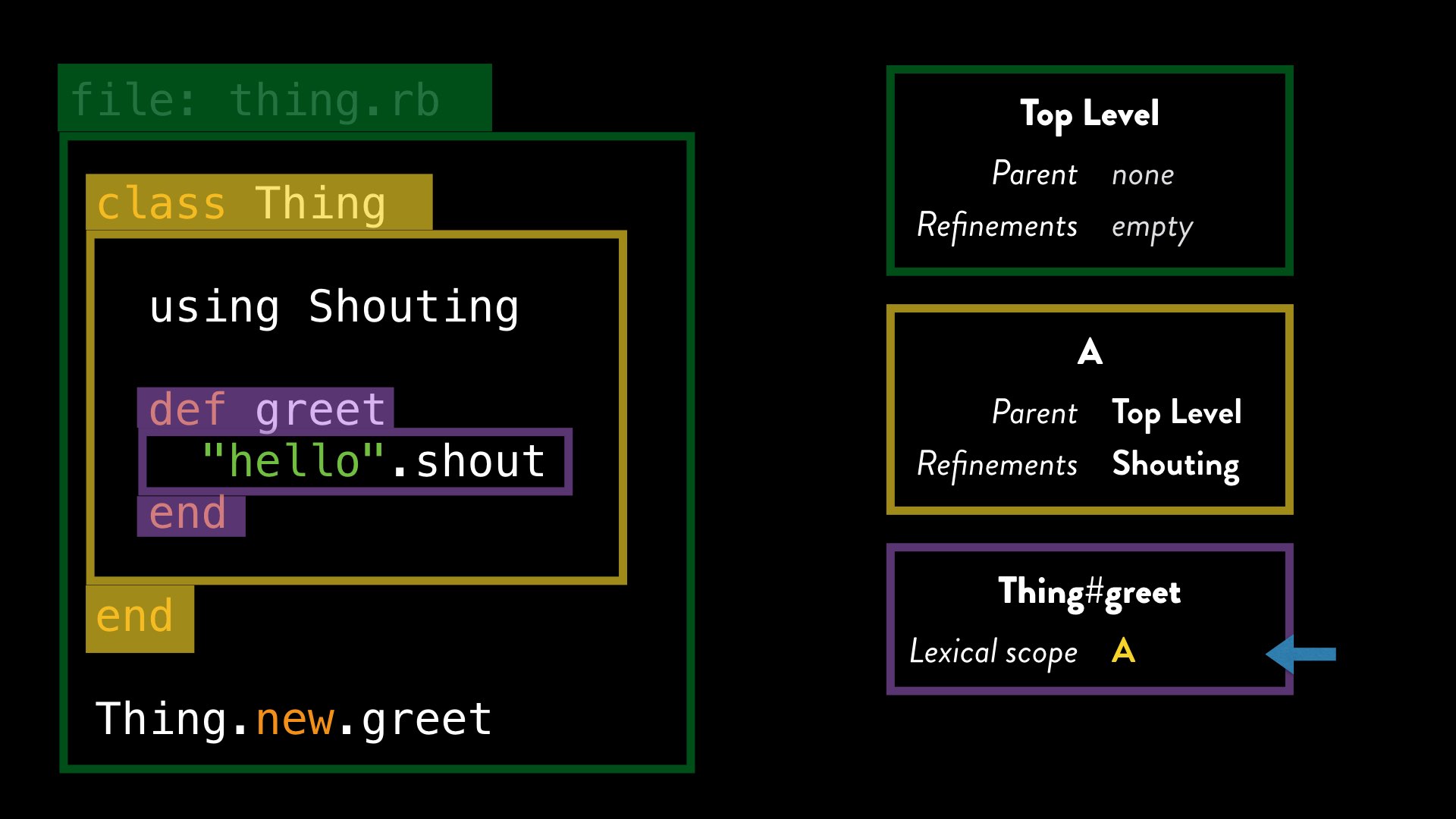

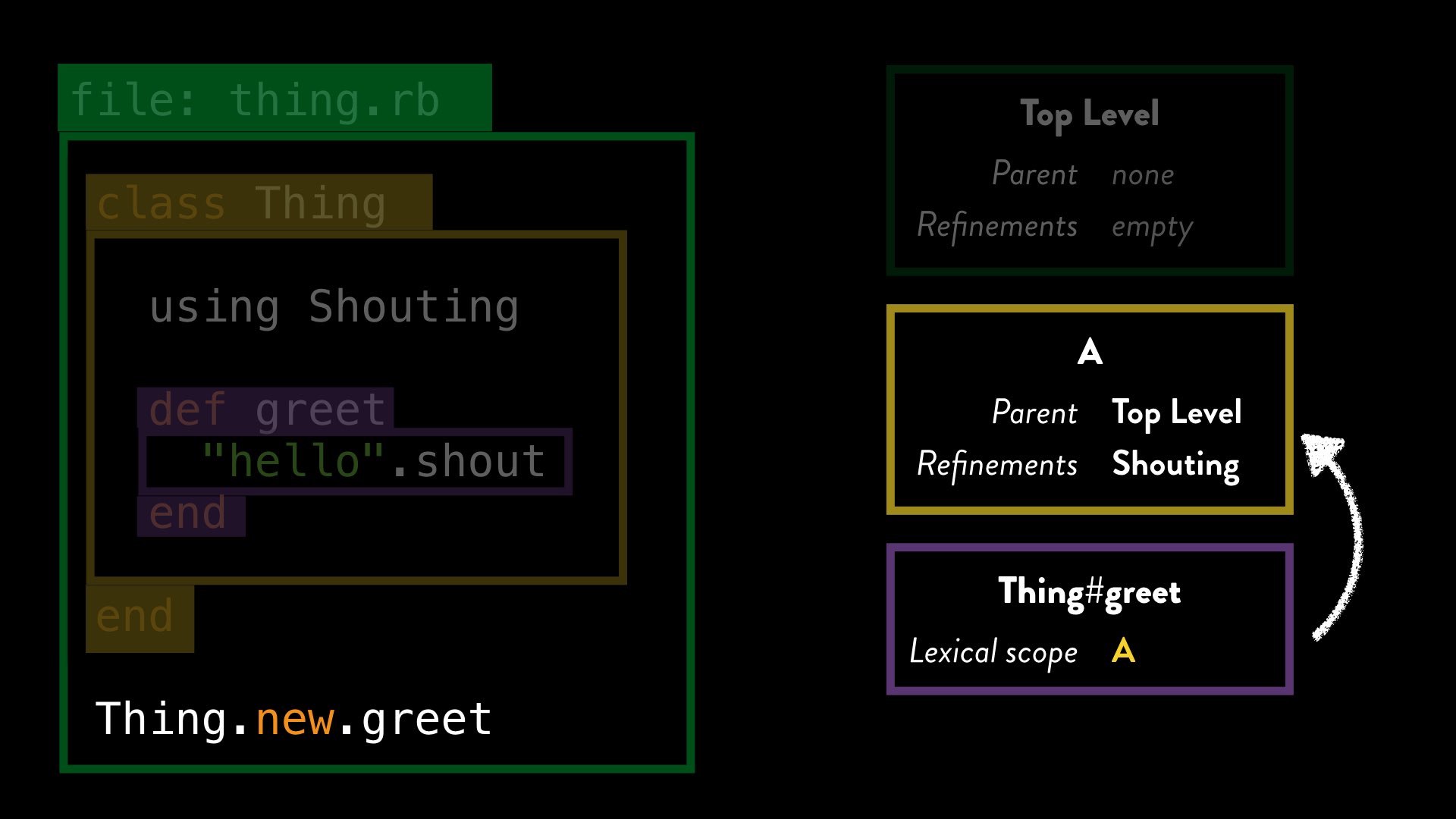

Here we are activating a refinement within a class, and defining a method in that class which uses the refinement. Later, we create an instance of the class and call our method.

We can see that even though the method gets invoked from the top level lexical scope – where our refinement is not activated – our refinement still somehow works. So what’s going on here?

When Ruby processes a method definition, it stores with that method a reference to the current lexical scope at the point where the method was defined. So when Ruby processes the greet method definition, it stores a reference to lexical scope A with that:

When we call the greet method – from anywhere, even a different file – Ruby evaluates it using the lexical scope associated with its definition. So when Ruby evaluates ”hello".shout inside our greet method, and tries to dispatch to the shout method, it checks for activated refinements in lexical scope “A”, even if the method was called from an entirely different lexical scope.

We already know that our refinement is active in that scope, and so Ruby can use the method body for “shout” from the refinement.

This gives us our fourth principle:

Methods are evaluated using the lexical scope at their definition, no matter where those methods are actually called from.

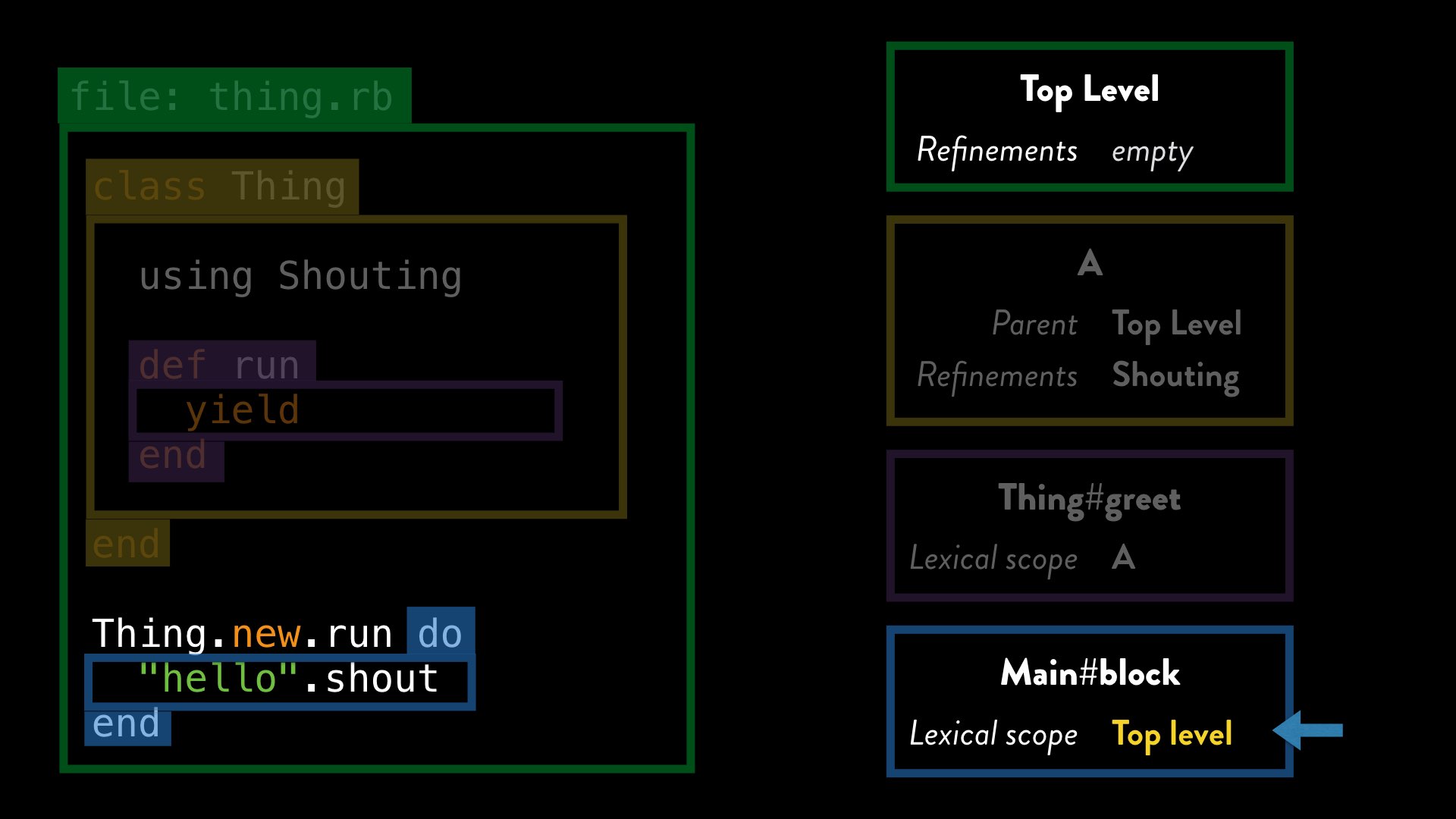

Lexical scope and blocks

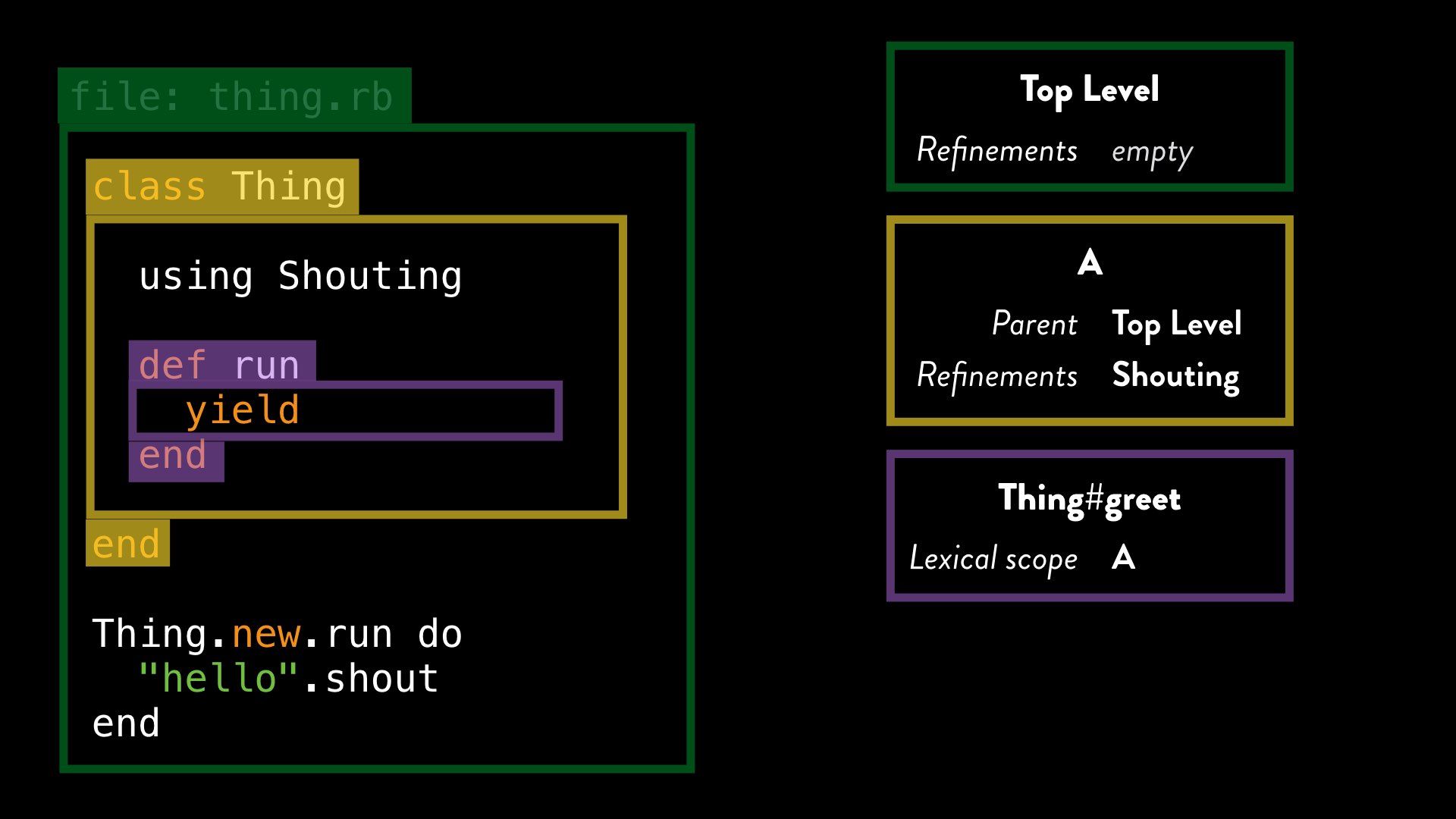

A very similar process explains why our block example didn’t work. Here’s that example again – a method defined in a class where the refinement is activated yields to a block, but when we call that method with a block that uses the refinement, we get an error.

We can quickly see which lexical scopes Ruby has created as it processed this code. As before, we have a nested lexical scope “A”, and the method defined in our class is associated with it:

However, just as methods are associated with the current lexical scope, so are blocks (and procs, lambdas and so on). When we define that block, the current lexical scope is the top level one.

When the run method yields to the block, Ruby evaluates that block using the top-level lexical scope, and so Ruby’s method dispatch algorithm finds no active refinements, and therefore no shout method.

Our final principle

Blocks – and procs, lambdas and so on – are also evaluated using the lexical scope at their definition.

With a bit of experimentation, we can also demonstrate to ourselves that even blocks evaluated using tricks like instance_eval or class_eval retain this link to their original lexical scope, even though the value of self might change.

This link from methods and blocks to a specific lexical scope might seem strange or even confusing right now, but we’ll see soon that it’s precisely because of this that refinements are so safe to use.

But I’ll get to that in a minute. For now, let’s recap what we know:

Lexical scope & principles recap

- Refinements are controlled using the lexical scope structures already present in Ruby.

- You get a new lexical scope any time you do any of the following:

- entering a different file

- opening a class or module definition

- running code from a string using

eval

As I said earlier: you might find the idea of lexical scope surprising, but it’s actually a very useful property for a language; without it, many aspects of Ruby we take for granted would be much harder, if not impossible to produce. Lexical scope is used as part of how Ruby understands references to constants, for example, and also what makes it possible to pass blocks and procs around as “closures”.

We also now have the five basic principles that will enable us to explain how and why refinements behave the way they do:

- Once you call

using, refinements are activated within the current, and any nested, lexical scopes - The nested scope hierarchy is entirely distinct from any class hierarchy in your code; subclasses and superclasses have no effect on refinements; only nested lexical scopes do.

- Different files get different top-level scopes, so even if we call

usingat the very top of a file, and activate it for all code in that file, the meaning of code in all other files is unchanged. - Methods are evaluated using the current lexical scope at their point of definition, so we can call methods that make use of refinements internally from anywhere in the rest of our codebase.

- Blocks are also evaluated using the lexical scope, and so it’s impossible for refinements activated elsewhere in our code to change the behaviour of blocks — or indeed, any other methods or code — written where that refinement wasn’t present.

Right! So now we know. But why should we even care? What are refinements actually good for? Anything? Nothing?

Let’s try to find out.

Let’s use refinements

Now, another disclaimer: these are just some ideas – some less controversial than others – but hopefully they will help frame what refinements might make easier or more elegant or robust.

The first will not be a surprise, but I think it’s worth discussing anyway.

Monkey-patching

Monkey-patching is the act of modifying a class or object that we don’t own – that we didn’t write. Because Ruby has open classes, it’s trivial to redefine any method on any object with new or different behaviour.

The danger that monkey-patching brings is that those changes are global – they affect every part of the system as it runs. As a result, it can be very hard to tell which parts of our software will be affected.

If we change the behaviour of an existing method to suit one use, there’s a good chance that some distant part of the codebase – perhaps hidden within Rails or another gem – is going to call that method expecting the original behaviour (or its own monkey-patched behaviour!), and things are going to get messy.

Say I’m writing some code in a gem, and as part of that I want to be able to turn an underscored String into a camelized version. I might re-open the String class and add this simple, innocent-looking method to make it easy to do this transformation.

class String def camelize self.split("_").map(&:capitalize).join end end "ruby_conf_2015".camelize # => "RubyConf2015"

Unfortunately, as soon as anyone tries to use my gem in a Rails application, their test suite is going to go from passing, not to failing but to ENTIRELY CRASHING with a very obscure error:

/app/.bundle/gems/ruby/2.1.0/gems/activesupport-4.2.1/lib/active_support/inflector/methods.rb:261:in `const_get': wrong constant name Admin/adminHelper (NameError)

from /app/.bundle/gems/ruby/2.1.0/gems/activesupport-4.2.1/lib/active_support/inflector/methods.rb:261:in `block in constantize'

from /app/.bundle/gems/ruby/2.1.0/gems/activesupport-4.2.1/lib/active_support/inflector/methods.rb:259:in `each'

from /app/.bundle/gems/ruby/2.1.0/gems/activesupport-4.2.1/lib/active_support/inflector/methods.rb:259:in `inject'

from /app/.bundle/gems/ruby/2.1.0/gems/activesupport-4.2.1/lib/active_support/inflector/methods.rb:259:in `constantize'

from /app/.bundle/gems/ruby/2.1.0/gems/activesupport-4.2.1/lib/active_support/core_ext/string/inflections.rb:66:in `constantize'

from /app/.bundle/gems/ruby/2.1.0/gems/actionpack-4.2.1/lib/abstract_controller/helpers.rb:156:in `block in modules_for_helpers'

from /app/.bundle/gems/ruby/2.1.0/gems/actionpack-4.2.1/lib/abstract_controller/helpers.rb:144:in `map!'

from /app/.bundle/gems/ruby/2.1.0/gems/actionpack-4.2.1/lib/abstract_controller/helpers.rb:144:in `modules_for_helpers'

from /app/.bundle/gems/ruby/2.1.0/gems/actionpack-4.2.1/lib/action_controller/metal/helpers.rb:93:in `modules_for_helpers'

You can see the error at the top there - something to do with constant names or something? Looking at the backtrace I don’t see anything about a camelize method anywhere?

Now we all know what caused the problem, but if someone else had written that code, I very much doubt it would be so obvious. And this is exactly the problem that Yehuda Katz identified with monkey patching in his blog post about refinements almost exactly five years ago.

Monkey-patching vs refinements

Monkey-patching has two fundamental issues:

The first is breaking API expectations. We can see that Rails has some expectation about the behaviour of the camelize method on String, which we obviously broke when we added our own monkey-patch elsewhere.

The second is that monkey patching can make it far harder to understand what might be causing unexpected or strange behaviour in our software.

Refinements in Ruby address both of these issues.

If we change the behaviour of a class using a refinement, we know that it cannot affect parts of the software that we don’t control, because refinements are restricted by lexical scope.

We’ve seen already that refinements activated in one file are not activated in any other file, even when re-opening the same classes. If I wanted to use a version of camelize in my gem, I could define and use it via a refinement, but anywhere that refinement wasn’t specifically activated – which it won’t be anywhere inside of Rails, for example – the original behaviour remains.

It’s actually impossible to break existing software like Rails using refinements. There’s no way to influence the lexical scope associated with code without editing that code itself, and so the only way we can “poke” some refinement behaviour into a gem is by finding the source code for that gem and literally inserting text into it.

This is exactly what I meant by limited and controlled at the start.

Refinements also make it easier to understand where unexpected behaviour may be coming from, because they require an explicit call to using somewhere in the same file as the code that uses that behaviour. If there are no using statements in a file, we can be confident – assuming nothing else is doing any monkey-patching – that Ruby will behave as we would normally expect.

This is not to say that it’s impossible to produce convoluted code which is tricky to trace or debug – that will always be possible – but if we use refinements, there will always be a visual clue that a refinement is activated.

Onto my second example.

Managing API changes

Sometimes software we depend on changes its behaviour. APIs change in newer versions of libraries, and in some cases even the language can change.

For example, in Ruby 2, the behaviour of the chars method on Strings changed from returning an enumerator to returning an Array of single-character strings.

# Ruby 1.9 "hello".chars # => #<Enumerator: "hello".each_char> # Ruby 2.0+ "hello".chars # => ["h", "e", "l", "l", "o"]

Imagine we’re migrating an application from Ruby 1.9 to Ruby 2 (or later), and we discover that some part of our application which depends on calling chars on a String and expecting an enumerator to be returned.

If some parts of our software rely on the old behaviour, we can use refinements to preserve the original API, without impacting any other code that might have already been adapted to the new API.

Here’s a simple refinement which we could activate for only the code which depends on the Ruby 1.9 behaviour:

module OldChars refine String do def chars; each_char; end end end "hello".chars # => ["h", "e", "l", "l", “o"] using OldChars "hello".chars # => #<Enumerator: "hello".each_char>

The rest of the system remains unaffected, and any dependencies that expect the Ruby 2 behaviour will continue to work into the future.

My third example is probably familiar to most people.

DSLs

One of the major strengths of Ruby is that its flexibility can be used to help us write very expressive code, and in particular supporting the creation of DSLs, or “domain specific languages”. These are collections of objects and methods which have been designed to express concepts as closely as possible to the terminology used by non-programmers, and often designed to read more like human language than code.

Adding methods to core classes can often help make DSLs more readable and expressive, and so refinements are a natural candidate for doing this in a way that doesn’t leak those methods into other parts of an application.

RSpec as a DSL

RSpec is a great example of a DSL for testing. Until recently, this would’ve been a typical example of RSpec usage:

describe "Ruby" do it "should bring happiness" do developer = Developer.new(uses: "ruby") developer.should be_happy end end

One hallmark is the emphasis on writing code that reads fluidly, and we can see that demonstrated in the line developer.should be_happy, which while valid Ruby, reads more like English than code. To enable this, RSpec used monkey-patching to add a should method to all objects.

Recently, RSpec moved away from this DSL, and while I cannot speak for the developers who maintain RSpec, I think it’s fair to say that part of the reason was to avoid the monkey-patching of the Object class.

However, refinements offer a compromise that balances the readability of the original API with the integrity of our objects.

module RSpec refine Object do def should(expectation) expectation.satisfied_by?(self) end end end using RSpec 123.should eq 123 # => true false.should eq true # => false

It’s easy to add a should method to all objects in your spec files using a refinement, but this method doesn’t leak out into the rest of the codebase.

The compromise is that you must write using RSpec at the top of every file, which I don’t think is a large price to pay. But, you might disagree and we’ll get to that shortly.

RSpec isn’t the only DSL that’s commonly used, and you might not even have thought of it as a DSL – after all, it’s just Ruby. You can also view the routes file in a Rails application as a DSL of sorts, or the query methods ActiveRecord provides. In fact, the Sequel gem actually does, optionally, let you write queries more fluently by using a refinement to add methods and behaviour to strings, symbols and other objects.

DSLs are everywhere, and refinements can help make them even more expressive without resorting to monkey-patching or other brittle techniques.

Onto my last example.

Internal access control

Refinements might not just be useful for safer monkey-patching or implementing DSLs.

We might also be able to harness refinements as a design pattern of sorts, and use them to ensure that certain methods are only callable from specific, potentially-restricted parts of our codebase.

For example, consider a Rails application with a model that has some “dangerous” or “expensive” method.

module UserAdmin refine User do def purge! user.associated_records.delete_all! user.delete! end end end # in app/controllers/admin_controller.rb class AdminController < ApplicationController using UserAdmin def purge_user User.find(params[:id]).purge! end end

By using a refinement, the only places we can call this method are where we’ve explicitly activated that refinement.

From everywhere else – normal controllers, views or other classes – even though they might be handling the same object – the very same instance, even – the dangerous or expensive method is guaranteed not to be available there.

I think this is a really interesting use for refinements – as a design pattern rather than just a solution for monkey-patching – and while I know there could be some obvious objections to that suggestion, I’m certainly curious to explore it a bit more before I decide it’s not worthwhile.

So those are some examples of things we might be able to do with refinements. I think they are all potentially very interesting, and potentially useful.

So, finally, to the question I’m curious about. If refinements can do all of these things in such elegant and safe ways, why aren’t we seeing more use of them?

Why is nobody using refinements

It’s been five years since they appeared, and almost three years since they were officially a part of Ruby. And yet, when I search GitHub, almost none of the results are actual uses of refinements.

In fact, some of the top hits are gems that actually try to “remove” refinements from the language!

You can see in the description: “No one knows what problem they solve or how they work.”! Well, hopefully we at least have some ideas about that now.

Breaking bad

I actually asked another of the speakers at RubyConf2015 — who will remain nameless — what they thought the answer to my question might be, and they said:

“Because they’re bad, aren’t they.”

As if it was a fact.

Now, my initial reaction to this kind of answer is somewhat emotionally charged, but my actual answer was more like:

“Are they? Why do you think that?”

So I don’t find this answer very satisfying. Why are they bad?

I asked them why, and they replied

“Because they’re just another form of monkey patching, right?”

Well – yes, sort of, but also… not really.

And just because they might be related in some way to monkey-patching – does that automatically make them bad, or not worth understanding?

I can’t shake the feeling that this is the same mode of thinking that leads to ideas like “meta-programming is too much magic” or “using single or double quoted strings consistently is a *very important thing*” or that something – anything – you type into a text editor can be described as “awesome” when that word should be reserved exclusively for moments in your life like seeing the Grand Canyon for the first time, and not when you install the latest gem or anything like that.

I am… suspicious… of “awesome”, and so I’m also suspicious of “bad”.

Slow?

I asked another friend if they had any ideas about why people weren’t using refinements, and they said “because they’re slow”, again, as if it was a fact.

And if that were true, then that would be totally legitimate… but it turns out it’s not:

““TL;DR: Refinements aren’t slow. Or at least they don’t seem to be slower than ‘normal’ methods”

So why aren’t people using refinements? Why do people have these ideas that they are slow, or just plain bad?

Is there any solid basis for those opinions?

As I told you right at the start, I don’t have a neatly packaged answer, and maybe nobody does, but here are my best guesses, based on tangible evidence and understanding of how refinements actually work

1. Lack of understanding?

While refinements have been around for almost five years, the refinements you see now are not the same as those that were introduced half a decade ago. Originally, they weren’t strictly lexically scoped, and while this provides some opportunity for more elegant code than what we’ve seen today – think not having to writing using at the top of every RSpec file, for example – it also breaks the guarantee that refinements cannot affect distant parts of a codebase.

It’s also probably true that lexical scope is not a familiar concept for many Ruby developers. I’m not ashamed to say that even though I’ve been using Ruby for over 13 years, it’s only recently that I really understood what lexical scope is actually about. I think you can probably make a lot of money writing Rails applications without ever really caring about lexical scope, and yet, without understanding it, refinements will always seem like confusing and uncontrollable magic.

The evolution of refinements hasn’t been smooth, and I think that’s why some people might feel like “nobody knows how they work or what problem they solve”. It doesn’t help, for example, that a lot of the blog posts you’ll find when you search for “refinements” are no longer accurate.

Even the official Ruby documentation is actually wrong!

This hasn’t been true since Ruby 2.1, I think, but this is what the documentation says right now. Nudge to the ruby-core team: issue 11681 might fix this…

UPDATE: since giving the presentation, this patch has been merged!

I think some of this … “information rot” can explain a little about why refinements stayed in the background.

There were genuine and valid questions about early implementation and design choices, and I think it’s fair to say that some of the excitement about this new feature of Ruby was dampened as a result. But even with all the outdated blog posts, I don’t think this entirely explains why nobody seems to be using them.

So perhaps it’s the current implementation that people don’t like.

2. Adding using everywhere is a giant pain in the ass?

Maybe the idea of having to write using everywhere goes against the mantra of DRY - don’t repeat yourself - that we’ve generally adopted as a community. After all, who wants to have to remember to write using RSpec or using Sequel or using ActiveSupport at the top of almost every file?

It doesn’t sound fun.

And this points a another potential reason:

3. Rails (and Ruby) doesn’t use them

A huge number of Ruby developers spend most if not all of their time using Rails, and so Rails has a huge amount of influence over which language features are promoted and adopted by the community.

$ fgrep 'refine ' -R rails | wc -l # => 0

Rails contains perhaps the largest collection of monkey-patches ever, in the form of ActiveSupport, but because it doesn’t use refinements, no signal is sent to developers that we should – or even could – be using them.

UPDATE: Very shortly before this presentation was given, the first use of refinements actually was added internally within Rails.

Now: You might be starting to form the impression that I don’t like Rails, but I’m actually very hesitant to single it out. To be clear: I love Rails – Rails feeds and clothes me, and enables me to fly to Texas and meet all y’all wonderful people. The developers who contribute to Rails are also wonderful human beings who deserve a lot of thanks.

I also think it’s easily possible, and perhaps even likely, that there’s just no way for Rails to use refinements as they exist right now to implement something at the scale of ActiveSupport. It’s possible.

But even more than this, nothing in the Ruby standard library itself uses refinements!

$ fgrep 'refine ' -R ruby-2.2.3/ext | wc -l # => 0

Many new language features, like keyword arguments, won’t see widespread adoption until Rails and the Ruby standard library starts to promote them.

Rails 5 has adopted keyword arguments and so I think we can expect to see them spread into other libraries as a result.

Without compelling examples of refinements from the libraries and frameworks we use every day, there’s nothing nudging us towards really understanding when they are appropriate or not.

4. Implementation quirks

There are a number of quirks or unexpected gotchas that you will encounter if you try to use refinements at scale.

For example, even when a refinement is activated, you cannot use methods like send or respond_to? to check for refined methods. You also can’t use them in convenient forms like Symbol#to_proc.

using Shouting "hello".shout # => “HELLO" "hello".respond_to?(:shout) # => false "hello".send(:shout) # => NoMethodError ["how", "are", "you"].map(&:shout) # => NoMethodError

You can also get into some really weird situations if you try to include a module into a refinement, where methods from that module cannot find other methods define in the same module.

But this doesn’t necessarily mean that refinements are broken; all of these are either by design, or a direct consequence of lexical scoping.

Even so, they are unintuitive and it could be that aspects like these are a factor limiting the ability to use refinements at the scale of, say, ActiveSupport.

5. Refinements solve a problem that nobody has?

As easy as it is for me to stand up here and make a logical and rational argument about why monkey-patching is bad, and wrong, and breaks things, it’s impossible to deny that fact that even since you started reading this page, software written using libraries that rely heavily on monkey-patching has made literally millions of dollars.

So maybe refinements solve a problem that nobody actually has. Maybe, for all the potential problems that monkey patching might bring, the solutions we already have for managing those problems – test suites, for example – are already doing a good enough job at protecting us.

But even if you disagree with that – which I wouldn’t blame you for doing – perhaps it points at another reason that’s more compelling. Maybe refinements aren’t the right solution for the problem of monkey-patching. Maybe the right solution is actually something like: object-oriented design.

6. The rise of Object-oriented design

I think it’s fair to say that over the last two or three years, there’s been a significant increase in interest within the Ruby community in “Object Oriented Design”, which you can see in the presentations that Sandi Metz, for example, has given, or in her book, or discussion of patterns like “Hexagonal Architectures”, and “Interactors”, and “Presenters” and so on.

The benefits that O-O design tends to bring to software are important and valuable – smaller objects with clearer responsibilities, that are easier and faster to test and change – all of this helps us do our jobs more effectively, and anything which does that must be good.

And, from our perspective here, there’s nothing you can do with refinements that cannot also be accomplished by introducing one or more new objects or methods to encapsulate the new or changed behaviour.

For example, rather than adding a “shout” method to all Strings, we could introduce a new class that only knows about shouting, and wrap any strings we want shouted in instances of this new class.

class Shouter def initialize(string) @string = string end def shout @string.upcase + "!" end end shouted_hello = Shouter.new("hello") shouted_hello.shout # => "HELLO!"

I don’t want to discuss whether or not this is actually better than the refinement version, partly because this is a trivial example, so it wouldn’t be realistic to use, but mostly because I think there’s a more interesting point.

While good O-O design brings a lot of tangible benefits to software development, the cost of “proper O-O design” is verbosity; just as a DSL tries to hide the act of programming behind language that appears natural, the introduction of many objects can – sometimes – make it harder to quickly grasp what the overall intention of code might be.

And the right balance of explicitness and expressiveness will be different for different teams, or for different projects. Not everyone who interacts with software is a developer, let alone someone trained in software design, and so not everybody can be expected to easily adopt sophisticated principles with ease.

Software is for its users and sometimes the cost of making them deal with extra objects or methods might not be worth the benefit in terms of design purity. It is – like so many things – often subjective.

To be clear – I’m not in any way arguing that O-O design is not good; I’m simply wondering, whether or not it being good necessarily means that other approaches should not be considered in some situations.

So what’s the right answer?

And those are the six reasonable reasons that I could come up with as to why nobody is using refinements. So which is the right answer? I don’t know. There’s probably no way to know.

I think these are all potentially good, defensible reasons why we might have decided collectively to ignore Refinements.

However… I am not sure any of them are the answer that most accurately reflects reality. Unfortunately, I think the answer is more likely to the first one we encountered on this journey:

Because other people told us they are “bad”.

Conclusion-ish

Let me make a confession.

When I said “this is not a sales pitch for refinements”, I really meant it. I’m fully open to the possibility that it might never be a good idea to use them. I think it’s unlikely, but it’s certainly possible.

And to be honest, it doesn’t really bother me either way!

What I do care about, though, is that we might start to accept and adopt opinions like “that feature is bad”, or “this sucks”, without ever pausing to question them or explore the feature ourselves.

Sharing opinions

Sharing opinions is good. Nobody has the time the research everything. That would not only be unrealistic, but one of the benefits of being in a community is that we can benefit from each other’s experiences. We can use our collective experience to learn and improve. This is definitely a good thing.

But if we just accept opinions as facts, without even asking “why”… I think this is more dangerous. If nobody ever questioned an opinion as fact, then we’d still believe the world was flat!

It’s only by questioning opinions that we make new discoveries, and that we learn for ourselves, and that — together — we make progress as a community.

The “sucks”/“awesome” binary can be an easy and tempting shorthand, and it’s even fun to use – but it’s an illusion. Nothing is ever that clear cut.

There’s a great quote by a British journalist and doctor called Ben Goldacre, that he uses any time someone tries to present a situation as starkly either good or bad:

“I think you’ll find it’s a bit more complicated that that.”

This is how I feel whenever anyone tells me something “sucks”, or is “awesome”. It might suck for you, but unless you can explain to me why it sucks, then how can I decide how your experience might apply to mine?

One person’s “suck” can easily be another person’s “awesome”, and they are not mutually exclusive. It’s up to us to listen and read critically, and then explore for ourselves what we think.

And I think this is particularly true when it comes to software development.

Explore for yourselves

If we hand most, if not all responsibility for that exploration to the relatively small number of people who talk at conferences, or have popular blogs, or who tweet a lot, or who maintain these very popular projects and frameworks, then that’s only a very limited perspective compared to the enormous size of the Ruby community.

I think we have a responsibility not only to ourselves, but also to each other, to our community, not to use Ruby only in the ways that are either implicitly or explicitly promoted to us, but to explore the fringes, and wrestle with new and experimental features and techniques, so that as many different perspectives as possible inform on the question of “is this good or not”.

If you’ll forgive the pun, there are no constants in programming – the opinions that Rails enshrines, even for great benefit, will change, and even the principles of O-O design are only principles, not immutable laws that should be blindly followed for the rest of time. There will be other ways of doing things. Change is inevitable.

So we’re at the end now. I might not have been able to tell you precisely why so few people seem to be using refinements, but I do have one small request.

Please – make a little time to explore Ruby. Maybe you’ll discover something simple, or maybe something wonderful. And if you do, I hope you’ll share it with everyone.